Childhood Heart Disease

PEN-Plus for People Living with Childhood Heart Disease

Nine-year-old children who survive acute rheumatic fever in low and lower-middle-income countries have a 20 percent chance of dying before their 15th birthday and a greater than 70 percent chance of dying before the age of 25. This tragedy is as medically unnecessary as it is unjust.

To address this gap in care, the NCDI Poverty Network is working with 22 resource-poor countries around the world to implement PEN-Plus, a proven integrated-care delivery model for severe, chronic noncommunicable diseases such as rheumatic and congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, and sickle cell disease.

For people living with childhood heart diseases, for example, PEN-Plus clinics provide specialized care close to home, critical medications, and money for food and transportation to clinic.

“I sought treatment but could not find a diagnosis. I was having serious trouble breathing and could feel and smell blood when I breathed. Today I am taking medicines and my life has improved a lot. In the years of my illness, I couldn’t walk. But today, I can walk, and anyone who doesn’t know me can’t tell I have a health problem.”

—Damarce Uwimana, a young mother living with rheumatic heart disease in rural Rwanda

Meet People Living with Rheumatic Heart Disease in PEN-Plus Countries

Childhood Heart Disease Stories

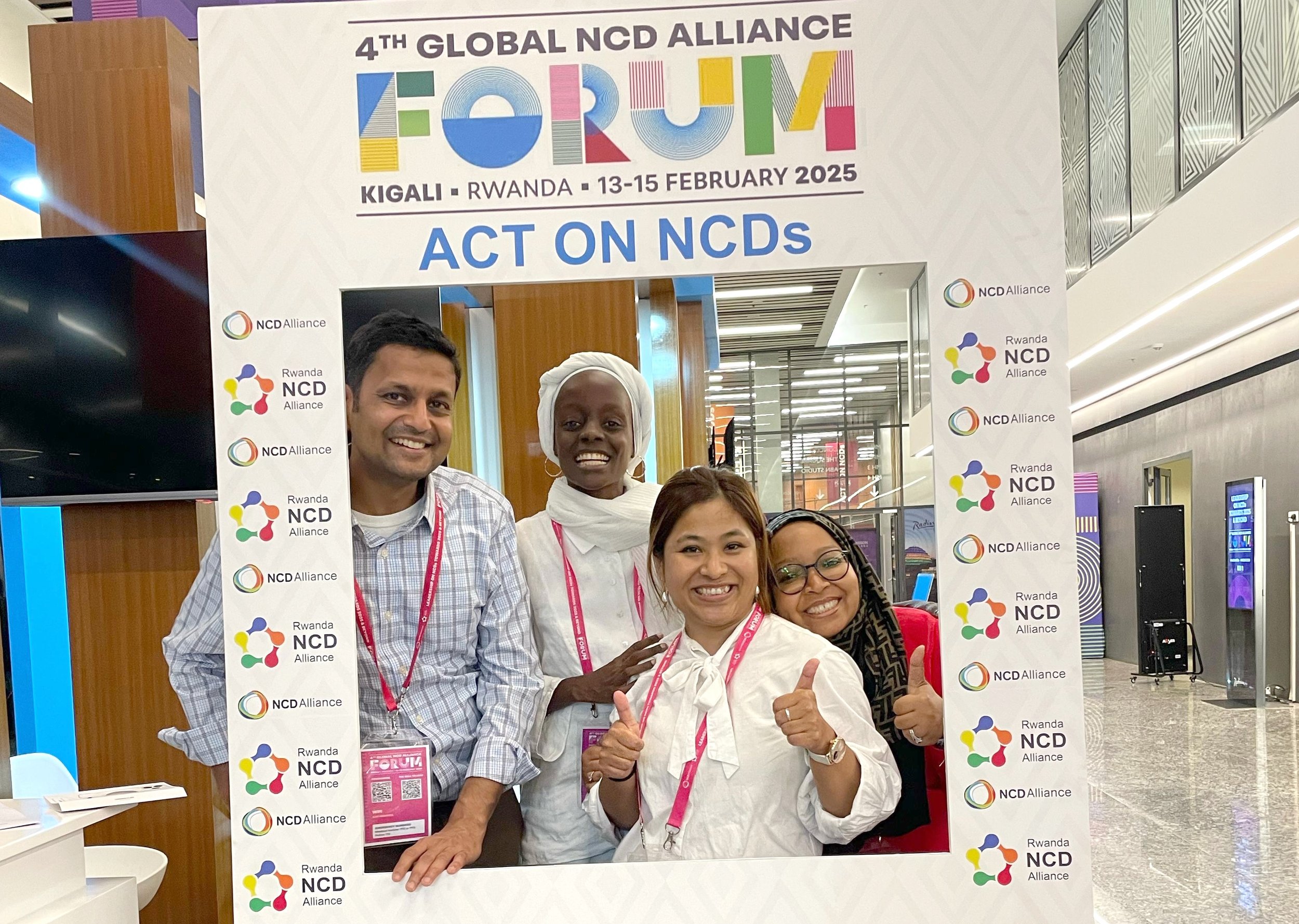

The NCDI Poverty Network’s recent week of advocacy in Rwanda included visits to two hospitals, a conference with more than 700 attendees, a panel with four expert speakers, and one recurring theme: the recognition that PEN-Plus is an effective model for mobilizing action and financing to increase access to care for people living with severe, chronic noncommunicable diseases.

The NCDI Poverty Network—through one of its co-secretariats, the Center for Integration Science in Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital—has joined UNICEF in publishing a report on the burden on noncommunicable diseases on children, adolescents, and young adults in South Asia.

The NCDI Poverty Network has published a French edition of PEN-Plus Clinical Tools and Programmatic Standards, a document that defines the diagnostic, treatment, and patient support services that compose PEN-Plus. Several francophone countries have already initiated PEN-Plus.

Camps that bring together young people living with a severe noncommunicable disease are showing that the benefits of integrated care can extend far beyond clinical settings. The first such camps—held this year in Rwanda and Zimbabwe—hosted young people with type 1 diabetes, sickle cell disease, and childhood heart disease.

During the East Africa Blood Disorders Leadership Forum, held in Nairobi in late October, Eunice Owino, a Voices for PEN-Plus advocate, spoke about her experiences living with sickle cell disease.

The PEN-Plus Partnership Strategic Plan (2025–2028) had its official launch at Springboard for Action, an event celebrating progress toward global access to care for people living with severe, chronic noncommunicable diseases. The NCDI Poverty Network hosted the event in New York City in September on the sidelines of the 79th Session of the U.N. General Assembly.

In Springboard for Action, a PEN-Plus celebration held in September on the sidelines of the 79th Session of the U.N. General Assembly, leaders from the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Africa, UNICEF, and Nigeria’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare all expressed their commitment to PEN-Plus. The event also featured a performance by the Broadway cast of Disney’s The Lion King.

The Network has published PEN-Plus Clinical Tools and Programmatic Standards, a document aimed at informing clinic planning, budgeting, and operations by providing a crisp definition of PEN-Plus clinical care, including the diagnostic, treatment, and patient support services available.

In recognition of World Sickle Cell Day on June 19, a Lancet Haematology editorial cited both PEN-Plus and the first International Conference on PEN-Plus in Africa as initiatives that can help ensure improved access to diagnosis, treatment, and care for people living with sickle cell disease in low- and middle-income countries.

For several years, the local health center had dismissed Fatmata Fofanah’s symptoms as the common cold. Yet those symptoms continued to worsen. “We noticed her heart was beating fast and she was short of breath,” said her mother, Mariama. “Even a few minutes of play would make her heart race.”

Following the International Conference on PEN-Plus in Africa, the NCDI Poverty Network hosted the first Voices for PEN-Plus Advocacy Summit. The event, held in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on April 26, brought stakeholders together to brainstorm ideas for increasing the scope and effectiveness of advocacy initiatives.

In advance of the International Conference on PEN-Plus in Africa, the NCDI Poverty Network team compiled research resources on PEN-Plus and other integrated-science healthcare delivery models.

For three years, João Mindo had difficulty walking, eating, and even breathing. It wasn’t until a PEN-Plus clinic opened in rural Mozambique that he received his diagnosis: rheumatic heart disease. Following mitral valve repair surgery in Maputo, the 14-year-old now receives care close to home.

NCDI Poverty Network team members carried the flag for PEN-Plus at the 8th World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, held in Washington, DC, in August. The event marked the first time the international conference took place in the continental United States.

The NCDI Poverty Network has produced “Language Matters,” a primer intended to sensitize PEN-Plus providers to the communication nuances involved in caring for people living with severe, chronic noncommunicable diseases.

In May, the NCDI Poverty Network, in partnership with the Rwanda Ministry of Health and with support from Team Heart, launched a national Cardiac Technical Working Group.

In May, eight PEN-Plus providers in Zimbabwe received initial training in performing and interpreting echocardiograms. Those eight providers—along with seven others—were also trained in managing heart failure.

“Becoming a health advocate and sharing my experience with the world has answered the questions that have plagued me since I was diagnosed as a child: Why do I have rheumatic heart disease? Why do I have to depend on medicine? What is the purpose in my life? I have found my purpose in health advocacy.”